http://www.defensemedianetwork.com/

By Dwight Jon Zimmerman - July 20, 2014

One U.S. Marine assigned to covert activities in Europe with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was Capt. Peter J. Ortiz, who was twice decorated with the Navy Cross. Here he receives his first Navy Cross from Adm. Harold R. Stark in London, U.K. Photo courtesy of Dick Camp

Approximately 80 officers and 200 enlisted men from the Marine Corps served in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. In that group was one of the most decorated Marines in World War II and the most decorated member of the OSS, Col. Pierre “Peter” Julien Ortiz, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, whose military career actually began in the French Foreign Legion. Tall, handsome, urbane, and sophisticated, Ortiz spoke 10 languages and was fluent in several, including French and Arabic. His decorations include two Navy Crosses, the Legion of Merit with Valor device, two Purple Hearts, the Ouissam Alaouite, five Croix de Guerre, the Croix du Combattants, the Médaille des Blesses, the Médaille des Evadés, the Médaille Colonial, Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, and Order of the British Empire, among others. His exploits during the war combined aspects of Errol Flynn, Chesty Puller, and James Bond.

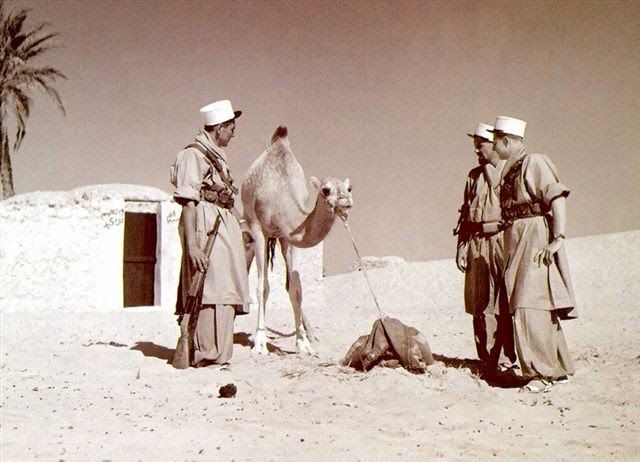

Ortiz was born in New York City in 1913 to an American mother and a French-Spanish father who was prominent in the French publishing industry. After a childhood spent in Southern California, his father sent Peter and his older sister, Inez, to French boarding schools to complete their education. Despite achieving good grades, Ortiz was bored with college, and in 1932, at age 19 and craving adventure, he enlisted in the French Foreign Legion. He found the adventure he sought in the Moroccan Rif, where he earned his first two Croix de Guerre fighting Rif Berbers.

Discharged in 1937 with the rank of sergeant, he returned to Southern California, where he worked in Hollywood as a technical adviser on war films. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Ortiz re-enlisted in the Legion and was commissioned a lieutenant. Wounded and captured by the Germans during the Battle of France in 1940, he successfully escaped after about a year-and-a-half as a POW, and eventually made his way back to the United States. Ortiz offered his services to the U.S. Army Air Corps, who promised him a commission. But impatient over the delays in processing his paperwork, on June 22, 1942, he enlisted in the Marines.

The Operation Union II team the day after the jump into occupied France, Aug. 2, 1944. From left: Sgt. John Bodnar, Maj. Peter J. Ortiz, Sgt. Robert LaSalle, Sgt. Fred Brunner, Capt. Frank Coolidge, and Sgt. Jack Risler. All except Coolidge were Marines. Photo courtesy of Laura Lacey

His presence in formation for the first time at Parris Island became a learning moment for everyone present when the drill instructor (DI) balefully noticed the decorations on recruit Ortiz’s chest. Two weeks after the DI had vocally satisfied his curiosity regarding the identity and provenance of said decorations, the Parris Island commander was writing to the commandant of the Marine Corps requesting confirmation of Ortiz’s service in the French Foreign Legion, noting Ortiz was a “unique new recruit” with “knowledge of military matters … far beyond that of a normal recruit” and recommended that Ortiz receive a commission. On Aug. 16, Ortiz was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps, retroactive from July 24, 1942.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Ortiz re-enlisted in the Legion and was commissioned a lieutenant. Wounded and captured by the Germans during the Battle of France in 1940, he successfully escaped after about a year-and-a-half as a POW, and eventually made his way back to the United States.

Initially, he was assigned as an assistant training officer at Camp Lejeune. Two months later, Ortiz was sent to the New River Parachute Training School. Having previously completed parachutist training in the Legion and with 154 jumps under his belt, Ortiz took his re-education with good humor, later saying, “The Legion had its way and the Marine Corps had the right way; I never minded jumping. Airplane travel always made me sick, so I was happy to jump out.”

In the wake of the successful Allied landings in French Northwest Africa in Operation Torch, because of his language skills and Légionnaire’s experience in the region, Ortiz received a promotion to captain and assignment to the OSS. On Jan. 13, 1943, he arrived in Morocco officially as assistant naval attaché and Marine Corps observer, Algiers. But that was just a cover. His real assignment was that of a member of an OSS team working with Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) along the Tunisian border in Operation Brandon.

In War Report of the OSS, the official history of OSS operations in World War II, Kermit Roosevelt wrote, “Participation in this British operation constituted the first OSS experience in sabotage and combat intelligence teams in front areas and behind enemy lines. That the jobs actually done by the handful of OSS men who joined in the SOE Tunisian campaign were not typical of future activity was due as much to the exigencies of the battle situation as to the misunderstanding of their function by the British and American Army officers whom they served.” In other words, instead of collecting intelligence and conducting sabotage, the teams were sent on reconnaissance missions and ordered to find and kill Germans.

In February, Ortiz was in Gafsa when the Battle of Kasserine Pass was launched. During the action Ortiz literally found himself traveling all across the battlefield. He witnessed the panicked flight of American soldiers during the opening hours of the German offensive, briefly fought with an armored reconnaissance unit from the British Derbyshire Yeomanry, then linked up and fought with elements of the American 1st Armored Division. Upon crossing paths with an old Légionnaire friend who was now a captain, Ortiz attached himself to his friend’s unit and fought a desperate action near Pichon.